A Complete Guide to Dyslexia and Learning Disorders with Difficulties

There are several difficulties in learning—the umbrella term is called SLD, specific learning disabilities. Out of that, why we give more importance to dyslexia is that dyslexia forms around 70% of the specific learning disabilities which we get to see in society. It is a language based learning disorder that affects reading and language skills.

Basically, the challenges will be seen in reading, writing, and then spelling. So we have to be very clear—this is not the term which we should be using for people who have been exposed to insufficient teaching or less exposure or inadequate exposure. So we should not confuse ourselves from that condition with dyslexia actually, and there is some genuine difficulty in children who have visual challenges and auditory hearing challenges—you know, they also have some difficulty in learning, but that is not dyslexia. It's a different entity altogether.

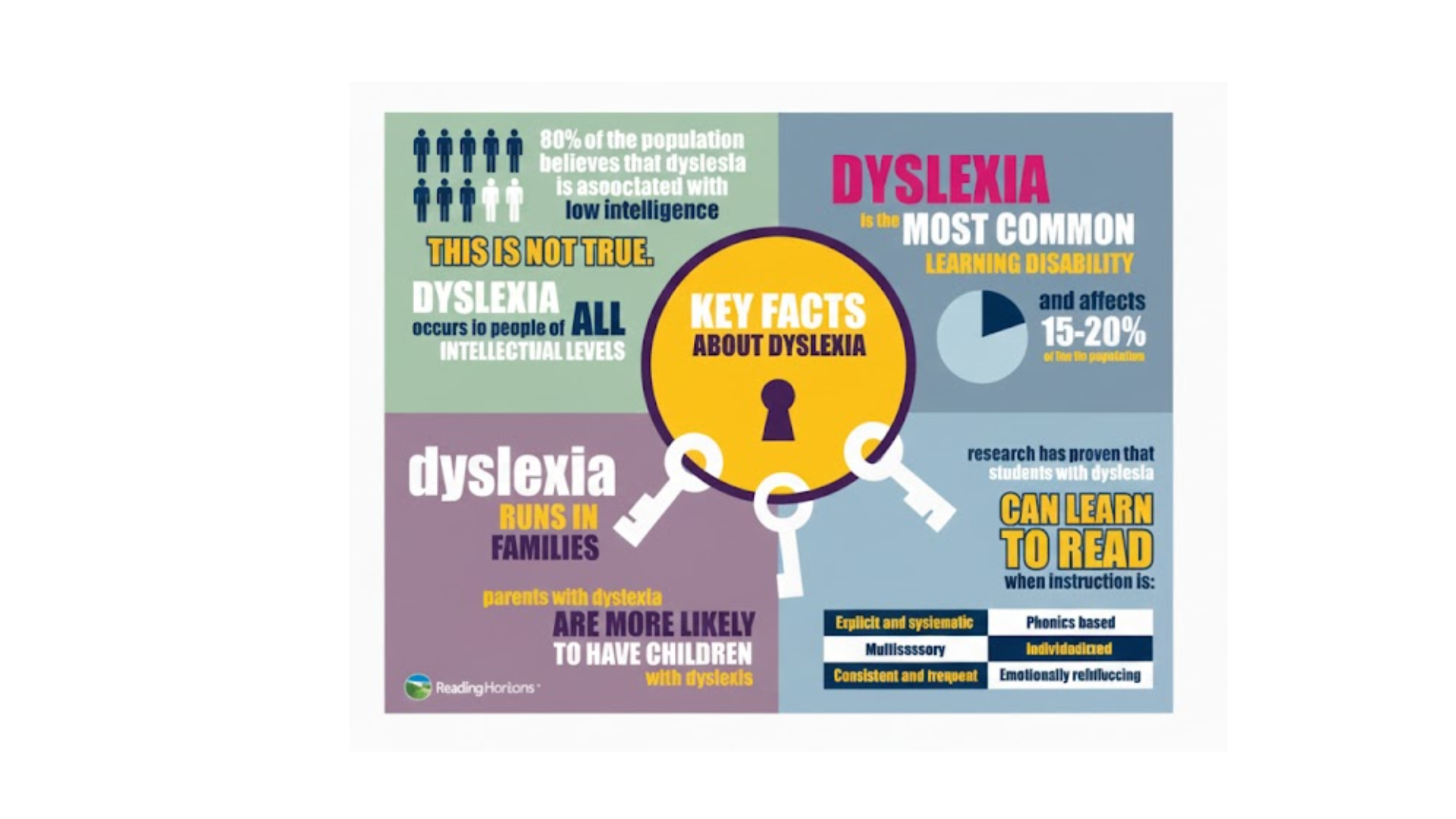

So how widespread it is—as I just began, it forms around 15 to 20% of the population. So most of the children with dyslexia,they have weak reading, weak spelling, and poor writing, you know, which we all are aware of actually. But out of all the children who receive these special education services in school and college programs, almost 50% are with learning disabilities. Out of that 50%, most of them more than 70%—have difficulty in reading, that is called dyslexia actually.

So it's a very prevalent condition which we can see anywhere—it does not have any conditions like, you know, autism. Autism is high in incidence in Far East nations—not like that. Dyslexia is almost evenly spread throughout humanity, so it's the most common learning disability. Dyslexia affects around 20% of the population, and the key facts include it runs in the family.

As we have discussed other neurological neurodiverse conditions, dyslexia also has a lot of heritable presentation. So that is the key thing to understand, and people even say, you know, people with dyslexia are having low intelligence. No, they are not. Low intelligence is entirely different. Dyslexia is different. People with dyslexia can be high achievers—not like a very small percentage in ADHD and autism, but here most people with dyslexia can really do very well in their life. Except for learning and reading, they can do very well in life, so it is not associated with low intelligence. And most of the children with dyslexia can read—you know, it is not that they can't read. They can be read with some specialized programs, which we'll discuss later in this presentation.

So it's an interesting thing to know—you know, people who graduate from school to college, higher education, postgraduation, and then they get into the job market, right? And then up the ladder they keep climbing the corporate careers. Out of them, only 1% are people with dyslexia. The number is very minuscule, a minority of people with dyslexia reaching the high levels in corporate careers. But people who are entrepreneurs—most of them, I would say around 40% of them—are dyslexic. Since most of them can't do this formal employment and then promotions and things like that, they choose to be entrepreneurs.

You know, they take their lives in their own hands. So almost 35 to 40% of entrepreneurs have some traits of dyslexia. That is what science says. So dyslexia is not tied to IQ. We know that, you know, for example, Albert Einstein—he is dyslexic, but his IQ is 160, which is just extraordinarily high and extremely rare. And people with good IQ and good academic careers, most of them are not aware about how dyslexia affects other people with dyslexia.

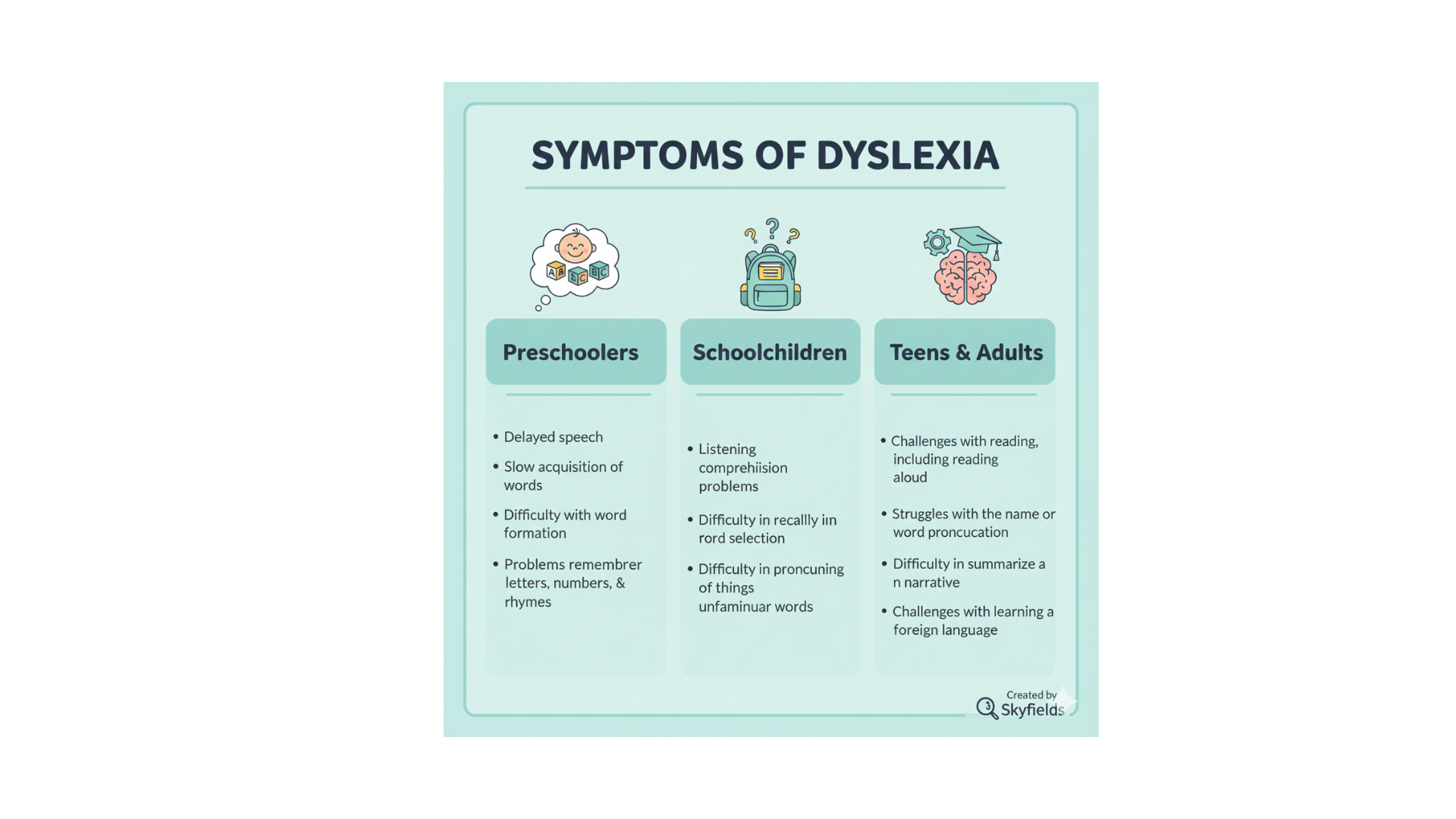

So symptoms—you know, dyslexia largely affects developmental disability. It affects children, but there are many people with adult dyslexia too, which we will look at in the later part of the presentation. The first thing is preschoolers—speech delay could be one sign to seek attention.

The slow acquisition of words, problems remembering letters, numbers, and rhymes—you know, they don't know how to fill in the words, and things like these are some signs which we can pick up from preschoolers. From school children, if you have like four or five words, they don't know what is the apt or appropriate word for this situation—they get confused. So that is one thing. And if you ask them to read one passage and then ask some questions based on comprehension skills, they find it really challenging. So that is the other observation. And then, you know, they have difficulty in recalling things actually, and pronunciation of certain words.

When it comes to teens and adults, they have significant difficulty in summarizing a narrative, challenges with learning a foreign language, you know. So that is why, you know, in India also—where we live, the state where I live especially—you know, people discuss whether the three-language policy is good or two-language policy is good. But what science says is that a single-language policy is a very good policy for children to grow up.

So wherever they are, if in Chennai, it could be Tamil; if in Delhi, it could be Hindi—you know, wherever we live, that single language is the best thing for a child, so that child can focus on the other STEM modules and other essential skills. So science says, especially for people with dyslexia, two languages, three languages—all the education boards across the world are giving concessions to not take second or third languages. Yes.

Here's a very interesting slide. I wanted to put all the symptoms of dyslexia into one slide, so I just chose this slide. So most of the people with dyslexia will be having difficulty in motor control. So they don't know—it's very difficult—the tripod holding, you know, using two fingers to hold a pen, using three fingers to hold a pen. All these basic holding techniques they find difficult, and most of them do have low muscle tone. So if they write, if they hold their pen for a very long time, their hand will be really aching. So they may not be able to hold it for a very long time.

When it comes to reading, you know, they read sometimes and then they don't comprehend, they don't understand. So they have to keep reading several times. So repeated re-education is also a technique to work with dyslexic children. In terms of spelling, they have a lot of confusion, you know. So the same phonetic sound with different meanings—they really get confused. And in terms of listening also, they don't know what noise to filter. In my room, air conditioning is on, fan is on, but I know what to filter and what to process. Children with dyslexia find it very difficult to filter and process.

And in terms of writing, again, there is something called dysgraphia. People who can read well but they cannot write well, you know, and then they just get lost. A very important symptom is spatial and temporal. For a right turn, they will take a left turn. Most of them do have this confusion. While we are driving, you know, we say we take a right turn, but we'll say it as a left. You know, most of them do have this kind of difficulty. That is why I said dyslexia is very prevalent among people.

It's not a very rare condition like autism or ADHD. There are several types of dyslexia. I don't want to go very deep into it, but I can just touch on what it is. The common form of dyslexia is phonological. You know, when a teacher teaches something, the auditory processing may not work. You know, there'll be delayed auditory processing or central processing delay. So that's called auditory dyslexia. That is very common among dyslexia.

The second common is visual dyslexia. So once they see some words, they really get confused, which is also called surface dyslexia. So some children do have auditory dyslexia and visual dyslexia together. So just look at this picture—you know, for me, if there is somebody who says "a," only capital A and the small a, uppercase and lowercase letters come to my mind. But for a child with dyslexia, this is called MMI, multiple mental images. They will get at least 100 forms of "a"—all the artistic a, calligraphic a, everything will come and present in their brain. What happens? It's complete chaos. So they don't know which "a" they have to zero in on, and then they just get stuck. This is what happens in predominantly dyslexic children.

Here you can see—the left picture, the brain picture, denotes the neurotypical brain, and the right one is a dyslexic brain. The left picture, you can see all the speech and language centers which need to work for better communication and better learning. Everything's intact. You can see something in the front part of the brain. The Broca's area is activated, you know, the parietal area is activated, the occipitotemporal—everything is at work to do the job. But for dyslexia, the parietotemporal, the word analysis and the word form—both are very, very obsolete. So the frontal part, the Broca's area, has to compensate for everything, and then it has to pull the things along. So that is why they have this processing delay at high level.

So dyslexia largely, you can branch them into two things. One is developmental, which is from the beginning, and then acquired could be because of some physical trauma, some heavy metal toxicity like mercury, lead toxicity, and injury, stroke—you know, all those things can cause dyslexia at some point in their life.